[alternate version of a review of Patrick Keiller's Tate show from ICON #110]

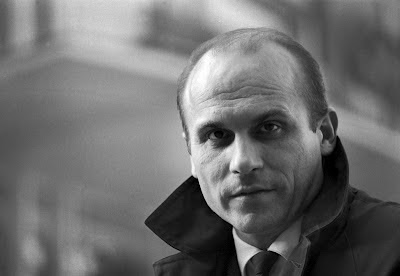

From a foreigner’s point of view, it is hard to find

an artist more parochial, more English (not even British) than Patrick Keiller.

This filmmaker, researcher, former architect, polymath, obsesses over Britain, the relation

between the land and economy, but strangely, it is not

making him provincial, because it’s hard to be provincial, if one’s obsessive

topic is the logic of western capitalism, hardly a local phenomenon. But Robinson, the character he created, is himself a kind of an exile, an outsider,

a queer, and this is precisely, what allows him to see “the problem of London”,

problem of the UK and subsequently, the whole western world, increasingly

endangered by the food and natural catastrophy.

The current show in Tate Britain

The exhibition itself is divided in eight sections, each a small platform, like a dry herbarium, with screens, canvases and memorabilia. And as if straight away answering the “but I haven’t seen any films of his” dilemma, he, the most ferocious chronicler of the present financial crisis, makes a shift and retraces us to the very beginning, the start of industrial revolution. One of the first objects in the show is the threshing machine, one of the first ever technologies introduced to the countryside, forerunner of mechanized production and the object of Luddite movement’s hate and destructive attacks. It’s huge and heavy – hardly a precursor to an Ipad. In his Robinson film trilogy, Keiller examined the tension between the rural and industrialBritain

The exhibition itself is divided in eight sections, each a small platform, like a dry herbarium, with screens, canvases and memorabilia. And as if straight away answering the “but I haven’t seen any films of his” dilemma, he, the most ferocious chronicler of the present financial crisis, makes a shift and retraces us to the very beginning, the start of industrial revolution. One of the first objects in the show is the threshing machine, one of the first ever technologies introduced to the countryside, forerunner of mechanized production and the object of Luddite movement’s hate and destructive attacks. It’s huge and heavy – hardly a precursor to an Ipad. In his Robinson film trilogy, Keiller examined the tension between the rural and industrial

We come back to the prehistory of modernity: the land

enclosure changed everything on those isles and in the perception of the world

as such. The show documents many movements of resistance to this act, mutinying peasants,

who saw it as a seizure of their freedom. From now on it’s impossible to

imagine common land with no possessions, where people live together and share,

although the show also documents attempts at independent communities. Since

then everything becomes a potential profit-maker, open to the speculations of the

market. Keiller shows how our thinking would be impossible without this

revolt, with signs of melancholy, even nostalgia after an unmechanised, rural

world, a ‘biophilia’, as he calls it, to the most basic forms of life. But it

is in a landscape after the humanity: we exploited everything, we had massive

food crisis, we disappeared, leaving behind the scorched earth. But even at his

most ‘biophiliac’, Keiller is not Tarkovsky gazing melancholically at the Zone, but an ironic,

politicized observer. With what delight and suppressed anger must have he

displayed the screens with the war economy (multiplying maps of the war zones,

photographs of roads, lanes, closures, private accesses, warnings). Maps of

Oxfordshire and Berkshire, primal locations of his films, overlap with maps of

Iraq – because maybe the truth of one can be found in the other. Robinson

believed he can best explore the world by walking, as if then the land unfolded

itself in an act of political-economical transformation. We can also only do as

much, images at the show haunt us, as if staring at them intensely enough, we

could see the molecular basis of the historical events.

This obsession pervades his work. In London (1992) he looked at the UK

Watch Patrick Keiller's London in Entertainment | View More Free Videos Online at Veoh.com

In Robinson in Ruins (2010), after his tormented and ferocious Robinson is released out of prison, put there after he invaded a closed military zone, he relocates to a caravan, where he collects all his previous research and then mysteriously disappears, leaving his legacy to the Institute. The film itself, narrated by the person from the eponymous 'Robinson Institute' (after the real death of Paul Scofield, role took up by Vanessa Redgrave with a perfect, emotionless, flat voice), previously involved with the now deceased Robinson's ex-lover, is supposed to be fragments of his own film-reels. What a beautiful way of building another level of mystery and shaking off rules of autorship Keiller takes his final epopey's element to, denying himself not only the auctorial voice, but also any involvement in what we see on the screen. And what we see is filmic rudiments, stripped to absolute basics: no music, not any non-diegetic score, only nature's images, in long, neverending shots, eternally contemplative, and, one could seriously ponder, an anti-thesis of Tarkovsky's wistful, metaphysical approach to static filming of nature.

In Robinson in Ruins (2010), after his tormented and ferocious Robinson is released out of prison, put there after he invaded a closed military zone, he relocates to a caravan, where he collects all his previous research and then mysteriously disappears, leaving his legacy to the Institute. The film itself, narrated by the person from the eponymous 'Robinson Institute' (after the real death of Paul Scofield, role took up by Vanessa Redgrave with a perfect, emotionless, flat voice), previously involved with the now deceased Robinson's ex-lover, is supposed to be fragments of his own film-reels. What a beautiful way of building another level of mystery and shaking off rules of autorship Keiller takes his final epopey's element to, denying himself not only the auctorial voice, but also any involvement in what we see on the screen. And what we see is filmic rudiments, stripped to absolute basics: no music, not any non-diegetic score, only nature's images, in long, neverending shots, eternally contemplative, and, one could seriously ponder, an anti-thesis of Tarkovsky's wistful, metaphysical approach to static filming of nature.And so in the latter, we feel the presence of God, who is 'looking' and 'directing' the image, when the human is absent (nature is never solitary, remember), it is left in its eternal "beauty and mystery"; but of course, we know: we feel such an immense, stubborn presence of Tarkovsky's own eye and sensibility, that we cant really stop thinking about it. Keiller is not giving himself this luxury of rich directing. Of course, like only the great ones do, he is capable of 'directing' the nature, but in his films there's no one looking. Nobody watches, God's dead (sic), people disappeared, even work as such is dead, replaced by machines, there's nothing, only a very uncanny presence of machines (let's not forget the lichens too, of course); and the anonymous, deadly Production going on, that could seemingly go on even after we're all dead (at this moment of crisis, which may also become a serious food crisis, so and so megatonnes of food, it's said, mostly oil seed rape used as biofuel, was not meant for human or animal consumption). Invisible hand of the market at play. Tricks of the trade. Nature's pure relentlessness.

'Robinson's Institute' is also such an

erudite delight all along - Warhol’s portrait of Goethe with Kippenberger’s The

Happy Ending of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika”, novel, from where Robinson was

born; Richard Hamilton intaglios of uncanny agricultural equipment, looking rather like some medieval miniatures,

fragments of Quatermass series – and dozens of books. But something

tells me that the copy of Borges’ Labyrinths

is there less important than, say Engels, Marx, Hobsbawm or Karl Polanyi. And

the ultimate message of the show may be to read and use this knowledge against

the state of things, rather than attend a psychogeography evening.