[a much longer version of an article first published in the Guardian's Review in print on 4.08.2012, an online version in here]

Ryszard Kapuscinski has been the biggest cultural Polish

pride abroad, a rare example of internationally recognised name, like ‘Milosz’

or ‘Polanski’, who gained fame due to his vivid literary reportages on power back

in the 1980s. Emperor, The Shah of Shahs, Soccer War gained interest not only

because of their authors unique position – a star reporter directly from the

darkness of the communist Poland, then in the midst of the martial law after a

failed workers revolution, but perhaps mainly due to their unusual style – very

personal, meticulous, literary, digressive. This wasn’t the usual way of

writing journalism and similarly, Artur Domoslawski’s stylish, digressive, written in the unusual present tense, nearly 500

pages long Kapuściński – The Biography is not a conventional biography. Both

the author and his hero – also, a friend, a master – stand out of what is

accepted in first – the cold war world and now – the post-communist neoliberal Poland

First of all, anyone familiar with the 'reportage' or 'travel' literature will know ‘colouring up’ is one of its commonest devices (think Robert

Byron, Curzio Malaparte, Bruce Chatwin, even Oriana Fallaci and others),

although it should be perhaps called just ‘literature’. And this was one of the

biggest paradoxes of Kapuscinski’s writing, but well showing the enigma this man

was. Some say, from today’s, ahistorical perspective, his journalism, from historiography point of view, is simplistic, even naïve “Lonely Planet” style travel writing for beginners, stating the obvious, making mistakes any serious research would wipe out. But

what does it matter some Berkeley professor who studied the life of Reza

Pahlawi for 30 years, has a better expertise than a poor, sleeping in a car and rags-wearing journalist from the Soviet Bloc

country had back in the 1960s? It just doesn’t stand.

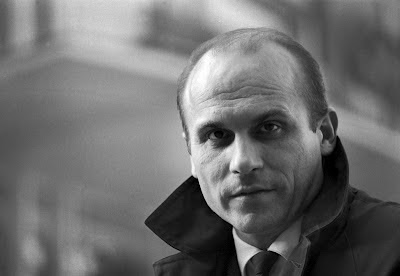

Domoslawski is trying to unpack his enigmatic hero, a

life-long shy, unconfident man, whose main preoccupation was to be liked (find me a photo without his trademark innocent smile): by

the regime, by colleagues, by readers, by critics. it reveals a man with high level of uncertainty. A huge section is devoted to

tracing the relative lack of criticism Kapuscinski’s experienced, which was set

precisely not to touch the taboo of his past: if they started to criticise him,

they’d also have to start a painful debate over the engagement of the current

elites in communism and perhaps change their current course: that would be too dangerous for the status quo.

The paradoxical shifts in this great reporter’s career

are worth studying not only for the fans of his writing, but because they show

in a nutshell the complications of Polish history. How come someone could be

first a dedicated socialist, highly engaged in building the new post-war

system, then its flagship reporter, traveling to all the revolutions across the

war, then a supporter of Polish opposition, who sat with workers in the

shipyards and then reluctant supporter of the transition, who nevertheless

never really felt comfortable in the post-89 Poland

To understand his importance it’s

enough to recall the controversies that arose upon the publication of Kapusciński – Non-Fiction (its original

title) in early 2010, both in Poland

Kapuscinski’s biography was tightly and intimately connected with various aspect of communist order and

cold war and contemporary politics in Poland Poland

The reason his past could possibly come as revelation is

because this mysterious man had to lay low and keep quiet about his involvement

in PRL from the start of the ‘democratic’ times. Between

the witch-hunt for the former agents, that started in the 2000s Poland by the paranoid right-wing government and

the support of the Iraq Iraq

This book, while letting all kinds of critical voices

– colleagues, friends, family, his professional critics, specializing in the

areas Kapuscinski stood out the most: Africa, Latino-American revolutions, Iran Africa , always identifying with the

weaker and politically misrepresented.

Domoslawski has lots of admiration for

his hero’s dedication and sacrifice. Yes, plenty of questions arise about what

was the real "cost" of the free traveling around the globe equipped with hard

currencies. However his contemporary critics can allege about the pay back he

had to do to the Party for his career – being a member of the intelligence,

namely – the poor, mostly hungry, often ill and endangered by death Kapuscinski

definitely didn’t gain much in comparison to his not only Western colleagues.

What did he gain in return? – speculate his friends in the book – ill and endangered by death, how did he himself measure his

‘success’ as a writer from some communist country? It must have been a tremendous

political passion and humanism, that made him such a profound critic of the

wars in Africa or, especially, the Cuban

revolution. He was wholeheartedly supporting Castro and rebelliants, and it was

his passion for socialism, not cold war anti-americanism, that gave him insight

into the negative role of USA Latin

America could’ve been written yesterday. Yet this mutual

appreciation had also darker sides: did Kapuscinski realise that his friends in

Politburo were involved eg. in bashing students in anti-Semitic witch-hunt in Poland

And the book, not only because the constant

speculations about the level of Kapuscinski’s engagement in the regime, reads

at times a bit like a John Le Carre novel. The question of identity, one’s own

image, of truth, of confabulation, shifts constantly and gains new meanings, turning the whole book into

one great quest in search of Kapuscinski’s personality. Who he was? Not even

the closest friends or family can answer this question.

His story remains

determined by his origins – born in the 1930s in Pińsk, part of the pale of

settlement, a Jewish town plagued by all possible atrocities of the WW2,

although his own life was not in danger, he experienced enough of misery –

holocaust, invasion first of Russians, then of the Nazis, and of Russians again, that it is believable

everything he’s done subsequently was inspired by this image. He was from a

poor family – and for the first time for people like him the PRL createrd

chances. He took it with all belief of the neophyte – as a youth and student

organizations activist, and then as debuting reporter. Maybe there his later

need for bigging himself up and confabulation came from, having to do with social class and complexes of being from a peripheral country? He had to become what

he aspired to be. One of his friends say “Rysiek produced a great work. However,

in order to do it, he had to create himself, his own image. In the mid-1980s in

America Poland

Domoslawski is not a mindless unanimous communism-monger, but points out the disadvantages where he must. He gives full details of his character's espionage (he had the code names “Poeta” and “Vera Cruz”), in particular the notorious case of him spying on the academic and reporter Maria Sten in Mexico

Kapuscinski is an especially neeeded character

today. In Poland Cuba , Iran

or Guatemala

When the moment came for

coming to terms with the crumbling Soviet Empire, he completely missed his

chance. Imperium (1993) (some of the many photos he did there here)is a book written in denial, a book, in which its author,

normally so engaged, who could’ve told us the most griping story of his own

engagement, disappears. Kapuscinski reacts with the biggest act of censorship -

the argument must’ve been that it would be announcing to people in the new Poland Poland Poland

No comments:

Post a Comment